My grandma likes to tell me, “Ever since you were a little girl, you always asked me about my past. ‘Where were you born, Nana?’ ‘How do you say this in French?’ You always asked. You wanted to know. You were curious about me.”

She was born in Algeria to French parents, one in a family of five girls. Odette, Lucette, Anne-Marie, Simone, and Yvonne. When she was a teenager, she got appendicitis, and her intestines were punctured during the operation. She spent nine months in the hospital, her mother traveling thirty minutes each way by bus to visit every day. She had four operations in that time. The nurses made her drink horse blood, and leeches tended to her wounds. That operation would cause a lifetime of health complications.

Later she fell in love with a half-French half-Cambodian parachutist who was stationed in Algeria. They found each other in newspaper classifieds and wrote back and forth for weeks before they ever met. They got married in Paris and started a life together.

Her family fled during the revolution, and they had to leave everything behind. I’ve never seen a photo of her as a child.

Soon a miracle baby was born. My grandma had intestinal tuberculosis and had been told, “It’s either you or the baby. Not both of you will make it.” She said, “I choose my baby. I am having this baby.” When the baby was born, people still thought she wouldn’t make it. A priest came to anoint the newborn with her last rites. That baby survived and became my mother.

With stories like these, how could I not have felt the magic of life, the fragility of existence, the wonder of the universe and our human journey? I could have sat by the fire of these stories all night. I did.

A child who was a keeper of stories

I’ve always been interested in my family’s storied past, particularly the stories of the powerful women who preceded me. I listened to their stories as if they were my stories. They were the stories that somehow lead to me. Each story felt like a miracle. It made me feel like a miracle, too. I could feel the life force being passed from one generation to the next.

I listened to the good and the bad, the devastating and the inspiring. I was hungry for their stories. I sat and listened with the kind of focus and entrancement of a kid watching cartoons. One story lead to another. I heard stories that no one in my family had ever heard. All I did was ask. And I stayed quiet enough to let the stories come out. I held their hands and urged them forward. My foremothers and I, we kept our eyes open until the rest of the city slept. When they finished, I closed those stories tight in my locket and grasped them at my heart when I lay in bed.

They told me the hard truth. They shared the beautiful mystery. They told me the stories you don’t tell children. They read me the love letters. They cried out their secrets. They uncovered their regrets. They shone light on their shame. I’m the only granddaughter and the only niece. I was a witness to their bravery and their vulnerability. The trust they gave to me in showing their true selves shaped me more than any other thing in my life.

I held stories. I held other people’s pain. They trusted me with their vulnerability. They trusted that I was strong enough to hear the intimate moments of their life.

I was the connector between each woman in my family. Where bitterness, insecurity, or fear arose in their relationships, I understood each side. They gave me the power to be a story vessel, a still pool of empathy. Or maybe I was born with the power, and they each sensed it. Maybe I was born with the power to draw the stories out. I wasn’t afraid of their sadness. I didn’t need them to be happy. Even when they told me tragic stories, the room didn’t feel sad, the world didn’t feel like a bad, scary place. We were both here. We were alive. And I saw that the woman in front of me who emerged from tragedy was someone of strength, of complexity. I learned what it meant to be human.

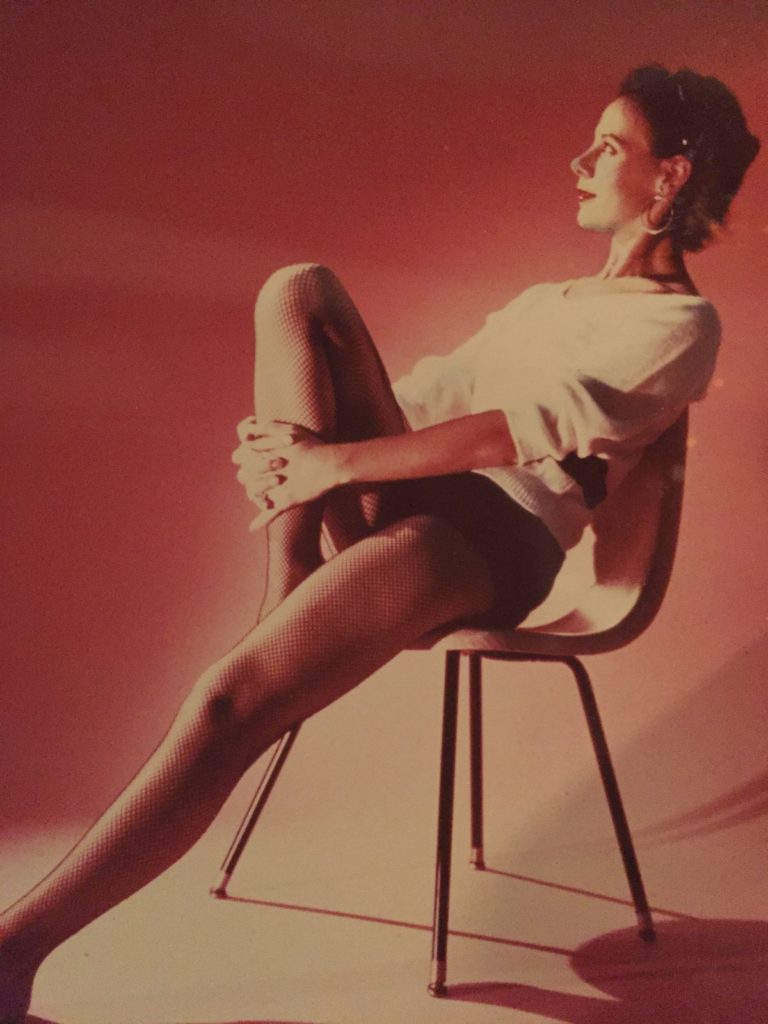

Who they were in the photos

It wasn’t just the stories I loved; it was the photos, too. When I looked at pictures of my mom, my grandmothers, and my aunt as young women, it was like being invited in on a juicy secret. I relished seeing the women they were in the photos. Their clothing was different, their hair, their makeup, their expressions. They sparkled, they held mysteries, they were bold in their beauty. The photos held the romance that old photos invoke. I tried to see myself in those young women, to understand who I wanted to be and who I could be.

I was an old soul. Who they were in the photos and in their stories helped me understand who they are now. I didn’t just want to see the person who was in front of me: the mother, the grandmother, the aunt. I wanted to see them when they were budding into themselves, with their whole lives in front of them. I wanted to see them before they started making choices for other people and changing themselves to fit other roles.

It was important for me to understand the choices that got them to this point. I loved seeing images of them before their choices ruled out some lives and ruled in others. When we say “yes” to one thing in life, we say “no” to something else. I could see it on their young faces. They were full of the possibility of “yes,” not yet weighed down by the yearning for all that they told “no.” Their becoming stretched ahead of them. Life was an invitation.

There is a sisterhood I long for with these mothers. A sense of continuity in our story. A sense that who they were made me possible. That I picked up where they left off. That their wildness, boldness, bravery, and raw zest for life were not lost but passed down to me.

We cross over generations and locations and exist together as the young women in the photos. I imagine us together as friends piling into the back of a taxi. I imagine us sitting on the beach laughing as the wind blows our hair into our mouths. We rub tanning oil on each other and read magazines, with coolers of fruity margaritas and fresh cut pineapple holding down our towels. I see us playing a board game while listening to music and reaching into bowls of candy, a couple of us passing around a cigarette. I see us in a bar dancing to Beyoncé, giving no time to the boys watching us. We take trips to the bathroom together to refresh our lipstick.

Who I was in the photos

Now when I look at the photos of them as young women, I gaze not forward into who I could become but backwards toward who I was. I know my own images of life as a young woman before marriage and motherhood exist in the past with theirs.

It’s easy to look back at their photos now and be sad for the young people I see. To see them with the knowledge that marriages ended, babies were lost, dreams unrealized, children estranged, hopes abandoned. To see them with the knowledge of the illnesses that would claim them. To see them knowing that they would walk the same self-destructive roads over and over, a chain of decisions and circumstances that derailed them from all they might have been.

I’m not actually sorry for how they’ve lived their lives or who they became. They’ve lived the breadth and depth of life. Dreams change, and life changes us.

The scary part is me with my own fear. I didn’t go to the unfamiliar, faraway place for college. I didn’t go to France to live and study abroad. I didn’t become a traveling journalist. I didn’t become a tri-lingual professor of comparative lit. I didn’t go to other countries to write my ethnography. I didn’t do the psychedelic drugs.

I see myself as that young person. For every “yes,” there were a dozen “no’s.” My yes’s sometimes brought with them a lot of pain. My yes’s leaned more toward growing roots and building community than flying the world chasing adventure like the woman in the photo thought she would.

I entered a relationship as a high school senior that tethered me to Mississippi and left me four years later with a lot of work of unbecoming.

I got married almost right out of college when I found the pure, healing love that my foremothers could not. I found a partner who respected and adored me. I knew we could have a good life together. I knew we could have a love different from any love I had ever seen in my family. I chose him as my person.

I entered an intense teaching program that chewed me up and spit me out, requiring a new process of healing and unbecoming.

I have made choices. I will make many more. I wanted the stability that my foremothers didn’t have. With that stability comes more room to think and to grow, to develop oneself. I traded manic joy and deep despair for steady contentment. I wanted balance.

I have a child now, and the window on yes’s in my life sometimes starts to feel very narrow. Sometimes the window is so streaked and cloudy that I can’t even see out of it to imagine what yes’s are available to me. Sometimes I feel like I’m in a room with no windows, and I just have to leave the house to remember that life exists outside of who I am as mom. When I breathe the fresh air, I breathe it as Catherine, not mom, even if my hands are pushing a stroller.

I am grateful for the choices I made and in love with the family I’m building, but every now and then I get this pang. I get a pining for the wild, the carefree, the adventure, the chase. I get this feeling that maybe I should have focused on building myself more before my choices committed me to other people. Maybe I should have left life more open-ended before getting so serious. I see the young woman in my photo, and I think, “Is she still there? Is she still in there somewhere? Did I give her enough time?”

Real women with complex stories

The women in the photos. I see them in their magnificence.

A woman who walked on hot coals and jumped out of airplanes and climbed mesas. A woman who said “no” to six men who proposed marriage, waiting into her early thirties for a love that she couldn’t deny. A woman who spent the first few years of her life traveling Europe and North Africa in a VW bug. A very Catholic Spanish woman who wore only black and had psychic powers, saw the future in her dreams. A girl who picked buttercups on her walk to school and always arrived to class late. A woman who has flown the world with a list of celebrities two pages long. A writer. A disco dancer. A ballerina. A muralist. A nutrition junkie. A mystic. A woman named after an opera singer.

I don’t want to romanticize those women and make them one-dimensional free-spirited nymphs. I see their stories. I see a woman who ran away from home in the middle of the night and drove across the country because home didn’t feel like home.

I see women married three times, not fully seen, appreciated, or honored by any man they married.

I see a woman whose father died in the coal mines of Kentucky and whose immigrant mother raised six children and lost one.

I see a woman whose mother was killed by an alcoholic in a car crash.

I see a woman whose husband left the house to go meet other women while his wife was in labor.

I see women who didn’t know that a college education was something that should be relevant to them but who learned all they could from life all the same.

I see a woman we lost to history, a Cambodian woman who birthed a child out wedlock with a French soldier, surrendered her baby, and later likely died in a concentration camp during Khmer Rouge.

I see a woman who traveled to America as a teenager with her brothers, leaving her parents and everything she knew behind in northern Italy.

I see a woman who had a baby as a teenager and declined a college art scholarship to take on the role of mom.

The women carried us

Catherine. Simone. Marie. Francisca Josefa. Adeline. Rosalina. Deborah. Dhang Thi Dom.

These are my people. These are the last four generations of women in my family. I hold their stories. I come from fighters, from the kind of resilience born of necessity, the grit not cultivated in classrooms.

The men were not there for the most part. You couldn’t count on them. They had mental illnesses, alcoholism, war, adultery, drugs, occupational accidents that killed their spirit if it didn’t bring death to their bodies. The men who were there were largely unsteady or perpetrators of violence. They disappointed, they hurt, they scared, they died. The best ones provided a steady income and loved the only way they knew how, with a lot of shame, fear, control, and moments of tenderness.

The women carried us. They were not perfect, but they did what they could with what they had. The women brought me here. And so when I look at their photos, I know the incredible pain under their joy. I feel their histories tattooed on the under sides of their skin.

However much pain piled in a wreckage behind them, I see them in the photos as young women choosing joy. They didn’t stop taking risks. They didn’t surrender. They started life new a hundred times.

They were stronger than fear, stronger than abuse, stronger than addiction, stronger than loss.

I come from the revolutionaries. I come from the women who persisted. I come from the women who made their own way when men did whatever they could to keep them their way. They don’t all have happy endings to their stories or happy middles for that matter, but they found some kind of happiness along the way, however fleeting and elusive.

I can never forget that I am the first woman in my family to graduate from college. I went on to get a Master’s. I can never forget that two generations ago a woman in my family had gasoline poured on her by her father. I can never forget that one generation ago a woman grew up in a home with wild parties, drugs, and instability, that there were times when her family had no home other than their car. Each generation was able to provide more security for their children than the last. More dysfunction rotates out of the cycle every year. What I am doing today is a miracle.

They fell so I can rise

The work that my foremothers did clearing the jungle made it possible for the next generation to journey farther and higher. They wrote the maps. They passed them down.

I stand on their shoulders. I stand so tall I can see above the jungle. I can touch the light. I am the queen. They are all with me chanting, “Rise, daughter, rise.”

Yes yes yes yes yes. Their voices rise.

I have so many yes’s left in me. My no’s do not define me. Who I chose not to be doesn’t define me. Each time I said “no,” I did so with intention and confidence. My no’s made the yes’s possible. Today my no’s feel more like power and self-determination than loss, more of a will to “be” than a wistful “could have been.”

Life is a yes. Motherhood is a yes. Womanhood is a yes. I will embody my yes. Yes, I will rise. Yes.

Comments +